The computers sitting on our desks are incomprehensibly fast. They can perform more operations in one second than a human could in one hundred years. We live in an era of CPUs that can perform billions of instructions per second, tens of billions if we take multi-cores into account, of memory that can transfer data to the CPU at hundreds of gigabytes per second, of disks that support streaming reads of gigabytes per second. This era of incredibly fast hardware is also the era of programs that take tens of seconds to start from an SSD or NVMe disk; of bloated web applications that take many seconds to show a simple list, even on a broadband connection; of programs that process data at a thousandth of the speed we should expect. Software is laggy and sluggish — and the situation shows little signs of improvement. Why is that?

I believe that the main reason is that most of us who started programming after, say the year 2000, have never learned how to make reasonable use of the computational resources at our disposal. In fact, most of our training has taught us to ignore the computer!

Although our job is ostensibly to create programs that let users do stuff with their computers, we place a greater emphasis on the development process and dev-oriented concerns than on the final user product. SICP contains a quote that I find to be a good summarization of the problem: “programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute.” Many programmers find that quote wise and inspiring, but users are not interested in reading programs, they’re interested in executing them, fast. We can’t make programs that run fast if we write them in a way that is only “incidentally” executable. The computer is not an implementation detail that can be abstracted away and ignored — it’s an integral part of the solution. A program that makes no room for the target machine in its design will inevitably run slower than one that does.

A common argument against taking the computer into account during the design phase of a program is “premature optimzation is the root of all evil.” Topics such as cache-friendliness, branch prediction, and parallelism are labeled as “optimization”, but really they should be labeled as “reasonable use”. Our users’ computers have resources and we should design our programs in a way that they use those resources.

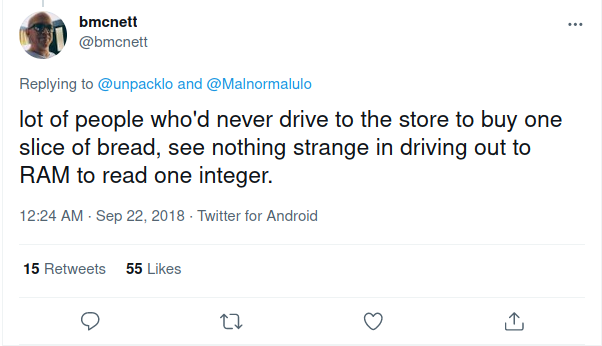

Take the CPU cache for example. A simple program that shows what a massive impact good cache usage can have on performance is to sum the elements of a matrix row-by-row vs. column-by-column (here’s a Rust Playground link that demonstrates this). In this example, the row-by-row is about 12–16 times faster than the column-by-column, even though they have same Big-O complexity. The difference in performance is not due to an abstract, computer science factor, but due to a very concrete one: better use of the CPU cache. The row-by-row approach brings 16 floats in cache and uses them all before going back to memory; by contrast the column-by-column approach also brings 16 floats, but only uses one of them before going back to RAM, leaving 15 values unused — that’s 94% waste.

There are a few things we should note about this example. First, the compiler did not optimize the code for us. We often hear that programmers can’t beat an optimizing compiler, but in this case we did. We only needed to change the order of the loops, but the Rust compiler which uses the LLVM backend, did not do it. Maybe the famed sufficiently smart compiler would, but for the foreseeable future, arranging data in a way that it can be processed efficiently will not be the compiler’s job — it’ll be ours. Second, we can’t get that speed-up without taking the actual hardware into account in our solution. We do not write code for abstract, idealized, or fictitious machines: we write code that runs on the CPUs of our users — Intel, AMD, Apple, etc. These CPUs have caches and it’s perfectly reasonable to write code that works well with the hardware rather than against it. Third, a 16x speed-up may only be a constant factor in complexity theory, but to a user it can be the difference between a program being pleasant to use and being extremely frustrating. Or the difference between a small and large AWS bill. And finally, we should not consider this to be an optimization: we’re making use of a resource that’s there. The users paid the full price of their CPU, let’s try and give them their money’s worth.

I expect that many will think of the old aphorism “make it work, make it right, make it fast” and argue that taking the machine into account when first writing the program is focusing on “make it fast” before we even got to “make it work”. I get that, but if we do things in order and make our program work and then make it right, when it’s time to make it fast, we often realize that our design works against us and we have to undo/redo a lot of the work we did to make the program work and to make it right.

For example, we may have arranged our data in a row-oriented fashion aka array of structs and we realize that in order to speed up our program we would need column-oriented storage, aka struct of arrays. Changing a program from one form to the other is a major re-architecture project, and one that may not be feasible if there’s a deadline approaching and that’s more slow software on the market and the aphorism becomes “make it work, make it right, dream of making it fast”.

So how do we write code that runs reasonably quickly on modern machines? We start by getting into the habit of not just thinking about the model of what we write, but also the mechanics: how many bytes are needed to represent a data structure? Are there many pointers that will cause cache misses? Is the data organized in a way that the branch prediction will be right often? Would it be easy to slice the work among multiple threads?

Another way is to start thinking in terms of batches and systems. Suppose we are writing a tokenizer for a programming language; if we think about tokens as completely independent pieces of data, each one needs to carry the string associated with the token (e.g., struct Token { tag: Tag, text: String, ... }). If instead we think of tokenization as a system and of tokens as dependents of this system, we can create a string pool in the tokenizer and tokens can have an index into the pool for their associated text. This saves memory by not having to duplicate strings and makes the tokens smaller, which means more can fit in one cache line.

Data-oriented design is an approach to programming that concerns itself with such questions. At the moment, most data-oriented design practitioners work in the game industry, but the insights are valuable in every field. (For example, Andy Kelly spoke highly of data-oriented design in the Zig 0.8.0 release notes.) If you’ve never been exposed to data-oriented design, it can be a bit of a shock — a lot of the common wisdom of programming (e.g., Uncle Bob’s SOLID principles) is eschewed and replaced with cold, hard engineering. It looks scary and different, but it’s what we need to do if we are to deliver software that is not orders of magnitude slower than it can be.

My thanks to Mathieu Lapointe for reading early drafts of this article.