In my last post I made the case that programmers should try and write their software in a way that makes reasonable use of the resources of the computer. By reasonable use, I didn’t mean to try and perform every crazy micro-optimization possible to extract every last speck of performance from the machine: instead, I meant to have mechanical sympathy, to write software in a way that works with the hardware rather than against it, and to take the specific problem into consideration when creating a solution.

That article had an example of how being mindful of the CPU cache can make one algorithm nearly 16 times faster than another, even though they have the same algorithmic complexity. I’ve been wanting to find a more real-world example, and this week, one feel in my lap.

A year ago, Mark Litwintschik wrote an article where he extracted the domain names from a 12 GiB gzip file containing 1.27 billion lines of JSON and created an ip,domain CSV file. That program was written in Python and took more than a day to run!

Last week, Mark wrote a follow-up article detailing a new program to do the same job, one written in Rust. Rust is a statically-typed language, it’s compiled to native code, and the compiler uses LLVM to apply many optimizations, so we’d expect this version to be faster. And it is: the Rust version processed the data in 48 minutes. After he shared his article on lobste.rs, Mark received suggestions to make the program faster and has since brought the processing down to 30 minutes. His new program is 50 times faster than his original — a much better use of the machine’s resources! And yet, when I initially read the article, I thought that 48 minutes sounded slow.

Thankfully, Mark’s article gave links to the dataset and to the third-party library he was using, and he shared his Rust code and the bash commands he used to execute his program. It made it very easy to replicate his experiment.

Mark’s program works in four phases:

- Read and decompress

- Parse JSON

- Call out to tldextract-rs to extract the domain name

- Write a line of output

The first thing I did was very simple: I timed how long it took to zcat the input. This would help me gauge how long steps 1 and 4 took together. I wanted to know if I was right to think that 48 minutes was slow or if my expectations were wrong.

$ time zcat rdns_xaa.json.gz >/dev/null

real 1m34.420s

user 1m34.047s

sys 0m0.364s

So roughly a minute and a half to decompress, read, and write. I didn’t think that parsing JSON would be much slower than decompressing a gzip file, so most of the time has to be spent in phase 3, extracting the domain name. Since the operation sounds quite simple and straight-forward (find the longest top-level domain suffix, take the substring to the left until a period or the beginning of the string is encountered), I suspected that something was probably being wasteful there.

Next, I ran Mark’s original program to know how long it took to run on my machine.

$ perf stat -dd ./target/release/tldextract rdns_xaa.json.gz >/dev/null

Performance counter stats for './target/release/tldextract rdns_xaa.json.gz':

1,644,491.19 msec task-clock # 1.000 CPUs utilized

8,526 context-switches # 0.005 K/sec

72 cpu-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

1,103 page-faults # 0.001 K/sec

6,678,553,292,544 cycles # 4.061 GHz (38.46%)

18,119,341,562,549 instructions # 2.71 insn per cycle (46.15%)

3,952,769,540,665 branches # 2403.643 M/sec (46.15%)

9,984,392,711 branch-misses # 0.25% of all branches (46.15%)

3,738,006,667,501 L1-dcache-loads # 2273.048 M/sec (46.15%)

39,713,107,241 L1-dcache-load-misses # 1.06% of all L1-dcache accesses (46.15%)

1,216,763,228 LLC-loads # 0.740 M/sec (30.77%)

26,340,299 LLC-load-misses # 2.16% of all LL-cache accesses (30.77%)

<not supported> L1-icache-loads

211,529,207,164 L1-icache-load-misses (30.77%)

3,738,968,599,010 dTLB-loads # 2273.632 M/sec (30.77%)

18,483,670 dTLB-load-misses # 0.00% of all dTLB cache accesses (30.77%)

38,106,464 iTLB-loads # 0.023 M/sec (30.77%)

382,508,684 iTLB-load-misses # 1003.79% of all iTLB cache accesses (30.77%)

1644.802173800 seconds time elapsed

1618.366720000 seconds user

26.137782000 seconds sys

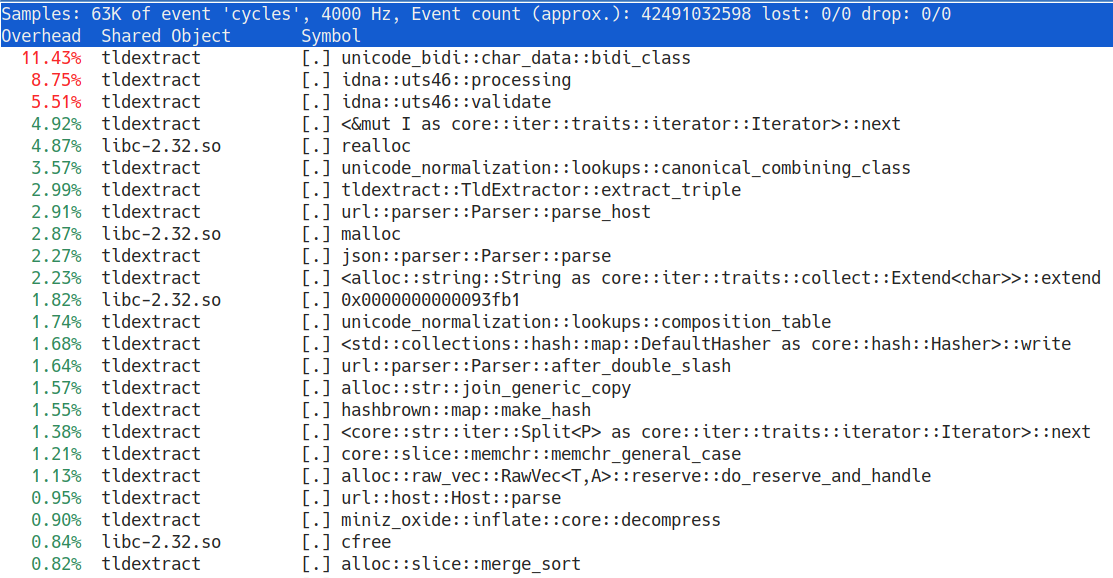

The program finished in 27 minutes on my machine. While the program was running, I also ran perf top to look at which functions were taking the most time.

When I skimmed the original program and the third-party library, I thought that they allocated a lot. For example, the std::io::Lines iterator allocates a new string for every line of input and when the line goes out of scope, it’s freed. Given the size of the input, that’s 1.27 billion allocations and deallocations. perf top shows malloc/realloc/free taking nearly 10% of the total execution time, so they’re a problem.

But the real big issue is in the third-party library to manipulate domains. Since domains are allowed to have Unicode in them, a lot of time is spent in IDNA code. But is that really necessary? Does the data that we manipulate require that we impose the extra cost of Unicode domain names upon us?

What I found by inspecting the data is that all the JSON objects contain only ASCII characters and only 20 objects out of 1.27 billion contain the substrings \u or \U (JSON unicode escape sequences). That means that the original program is using a library that makes processing every line slower for the benefit of only 0.00000157% of the lines. Instead of solving the generic case, let’s solve the common case.

$ parallel "zcat {} | grep -P '[^\000-\177]' | wc -l" ::: rdns_xa*.gz

0

0

0

0

$ parallel "zcat {} | grep -iF '\u' | wc -l" ::: rdns_xa*.gz

14

1

5

0

So given what we know, here’s the plan for a (hopefully) faster program. Like the original program we’ll use flate2’s GzDecoder to decompress the data. We are not going to use the lines iterator, instead we’re going to use the method BufReader::read_line which allows us to re-use the same buffer, so we only need to allocate once for all the lines. When we have a line, we’re going to do a quick linear search for the substring \u; if it’s found, we write that line to a file called rejected.json that we can process separately and move on to the next line. We’re going to use serde_json instead of json, because it’s a bit faster. To find the top-level domain, we’ll create a HashSet of all the domain suffixes (obtained from here) and we’ll find the longest suffix we can; once we have that suffix, we can extract the string to its left until we find a period or the beginning of the string. Finally, we write out to stdout, but not with println!, but with a pre-locked Stdout object.

$ perf stat -dd ./target/release/vfb-tldextract public_suffix_list.dat rdns_xaa.json.gz rejected_xaa.json >/dev/null

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627471863\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.39\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627447667\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.40\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627444989\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.43\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627486727\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.45\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: processed 310673926 lines (14 rejected) in 155.272128427s

Performance counter stats for './target/release/vfb-tldextract ../tldextract/public_suffix_list.dat ../tldextract/rdns_xaa.json.gz rejected_xaa.json':

155,270.78 msec task-clock # 1.000 CPUs utilized

451 context-switches # 0.003 K/sec

1 cpu-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

345 page-faults # 0.002 K/sec

631,384,933,925 cycles # 4.066 GHz (38.46%)

1,803,019,603,887 instructions # 2.86 insn per cycle (46.15%)

365,196,577,639 branches # 2351.998 M/sec (46.15%)

2,314,559,123 branch-misses # 0.63% of all branches (46.15%)

379,148,826,483 L1-dcache-loads # 2441.856 M/sec (46.15%)

2,166,436,251 L1-dcache-load-misses # 0.57% of all L1-dcache accesses (46.15%)

75,583,470 LLC-loads # 0.487 M/sec (30.77%)

25,064,718 LLC-load-misses # 33.16% of all LL-cache accesses (30.77%)

<not supported> L1-icache-loads

300,858,674 L1-icache-load-misses (30.77%)

379,351,678,372 dTLB-loads # 2443.162 M/sec (30.77%)

105,344 dTLB-load-misses # 0.00% of all dTLB cache accesses (30.77%)

506,821 iTLB-loads # 0.003 M/sec (30.77%)

2,868,354 iTLB-load-misses # 565.95% of all iTLB cache accesses (30.77%)

155.275422832 seconds time elapsed

154.847572000 seconds user

0.423987000 seconds sys

Now the final test, how long does it take to transform the four shards in parallel?

$ time /usr/bin/ls rdns*.json.gz | xargs -P4 -n1 -I{} sh -c './vfb-tldextract public_suffix_list.dat {} {}.rejected.json >{}.csv'

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627442231\",\"name\":\"41.185.37.10\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627473254\",\"name\":\"41.185.37.11\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627458666\",\"name\":\"41.185.37.12\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627479199\",\"name\":\"41.185.37.13\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627439294\",\"name\":\"41.185.37.14\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627471863\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.39\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627447667\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.40\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627444989\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.43\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627486727\",\"name\":\"152.149.215.45\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: cannot deserialize this line: "{\"timestamp\":\"1627490888\",\"name\":\"210.35.32.3\",\"type\":\"ptr\"}\n"

vfb-tldextract: processed 310673940 lines (0 rejected) in 184.360843703s

vfb-tldextract: processed 310673926 lines (14 rejected) in 184.376276827s

vfb-tldextract: processed 310673939 lines (1 rejected) in 184.705608281s

vfb-tldextract: processed 310673935 lines (5 rejected) in 188.207680141s

real 3m8.222s

user 11m53.263s

sys 0m16.673s

It’s slower than just one shard at a time (I haven’t yet investigated why that is; my guess is that we’re maxing out the write speed of the disk) but still nearly 10x faster than the original program. And I think we did things that most programmers would be able to do:

- Get a base line for how fast we can

zcata file - Use

perf topto find some bottlenecks that can be addressed - Look at the data to understand what the common case is

And I think that the final program is something that most people reading this would probably have been able to do themselves.

If you’d like to look at my code, it’s available on Github.